The Travel Bug

I'm writing this looking out my studio window in Vermont at a snow-covered, all-white landscape of road and field. It's 0 degrees outside, according to my porch thermometer.

A week ago I was in Elbow Cay, Bahamas, standing in the warm sun on the public dock, waiting to catch a ferry to Abaco Island and then a flight home.

That morning I saw a distance of blue water, green villas, sailboats, and pink clouds.

Susan Abbott, "Tangerine Stall, Dominican Republic"

Here in the U.S., I've worked in Maine, New York, Florida, Oregon, Washington state, Virginia, Baltimore, the Eastern Shore, and all around my home state of Vermont.

Susan Abbott, "Farm by the Inlet, Maine"

Some of these places, like Paris, and Provence, I've returned to over and over.

I've taught and painted in the same village in the Luberons every summer for the past twenty years, and been to Paris close to fifteen times over that same period.

Susan Abbott. "Path to Ruins, St. Saturnin les Apt"

Susan Abbott, "Blue Sunday"

I'm used to this moving around, and changing of climates and views.

For four months of the year I travel to paint on my own and teach art workshops in the U.S. and abroad.

Over the last decade, I've hauled my French easel to India, France, Italy, Spain, England, Canada, the Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic.

Susan Abbott, "Big Cloud, PEI"

Susan Abbott, "Tractor and Silo"

Susan Abbott, "The Seine at Musee D'Orsay"

By now you'd think I'd be fluent in French, but unfortunately I can only stutter the basics.

At home, I don't take the time for a language class, and when I'm in France, I interact only with my American students.

The rest of the time, I'm drawing in my sketchbook, or looking at art in museums, or painting, or walking solo. To learn a language, you have to speak it.

Sketchbook from Paris

Painting near Les Bassacs, Provence

I'm not proud of these art blinders I wear, and wouldn't recommend them to other Americans abroad.

They limit my experience, and therefore my understanding, of other cultures, and keep me in my own head, looking only at what's right in front of me.

This focus on painting specializes and limits my travel. I'm like the software programmer in London for a conference who takes no time to see Trafalgar Square.

Painting in Hope Town, Bahamas

This workaholic narrow-mindedness is the reality of how I, and I suspect many other, painters travel.

Books about Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent describe them painting during "working vacations".

Homer returned winter after winter to Florida, Cuba, Bermuda and the Bahamas, and Sargent took off regularly on painting expeditions all over the Mediterranean.

John Singer Sargent, "Melon Boats"

Yet in their paintings you can sense these artists' great enjoyment in their surroundings. You can feel the pleasure they took in the people, landscape, architecture, and colors they saw, which were so different from their Maine and London homes.

Both artists seem fully engaged, fully alive, painting these travel watercolors.

Claude Lorrain, "Landscape with Cephalus"

In the 1800's, Turner and many other British landscape painters, sketchbooks and watercolors in their rucksacks, hiked over the Alps on their way to Rome and Venice.

They crossed paths with German artists, their heads full of Wordsworth and Lord Byron, making their slow way to England's Lake District.

Matisse, "The Marabout, Tunisia", oil on linen

In the early 1800's, Camille Corot followed the footsteps of so many other French artists to Italy.

Rome was a mecca for European and American painters and sculptors until the 19th century.

Then Paris became the daydream of young artists from all over the world--followed by New York in the 1940's, and Berlin in the 2000's.

Winslow Homer, "Artists Sketching" (detail)

Sometimes artists travel for very practical reasons.

They need to find new markets for their work, escape war, study and instruct, or paint plein air in a hospitable climate.

Henri Matisse, "Seated Riffian"

We want to fall in love with how another culture looks and sees, with paintings from another place, and artists from another time.

And we learn to tolerate the feelings of vulnerability and loneliness that accompany solitude in a strange place.

Hopper, "Stairway at 48 Rue de Lille"

Before he turned thirty, Hopper managed to make two more painting trips back to the French capital.

He become a Francophile, fluent in French, a reader of Baudelaire and Victor Hugo, steeped in the characters and scenes of Paris.

His memory was full of the hundreds of paintings he had studied in the Louvre, and all that he had seen along the boulevards, in parks, theaters and cafes.

Edward Hopper, "Bridge in Paris"

But what Hopper had learned in Paris, painting along the luminous Seine, reading evocative Symbolist poetry, watching French films about alienation--all those things that weren't Nyack--never left him.

Howard Hodgkin, "Bombay Sunset"

Travel is a spark plug that can generate energy and direction--but an artist's work is more about routine than inspiration.

On our home ground, we face the patient building of personal imagery day after day and year after year, trying the same thing, with slight variations, over and over.

Susan Abbott, "Night Ride"

But Instead of practicing French, I'm usually practicing how to paint, standing at my easel in a lavender field or sitting on a quay next to the Seine.

My body language says, "Don't talk to me, Frenchmen, I am trying to figure out what to do with these brushes and palette..."

Painting in Viens, Provence

Traveling to teach, or paint, or look at art, I often miss the big attractions.

In the Bahamas I was staying fifty feet from a pristine beach with warm, turquoise waters and some of the best snorkeling in the islands. In three weeks, I walked on this beach for fifteen minutes, and stuck my toe in the water once.

Instead of enjoying this paradise of pink sand, I could be found most days dragging my suitcase full of art supplies around the hot sidewalks of the settlement, looking for a good motif.

Winslow Homer, "Fishing Boats, Key West", watercolor

Given the volume and quality of the watercolors they produced, which are ranked as the greatest and most innovative in this difficult medium, I'd say the emphasis when describing their trips should be on "working" rather than "vacation".

John Singer Sargent, "Cafe, Venice"

Why have artists always traveled so much? Like spice merchants or cloth traders, many Medieval and Renaissance artists followed well-worn routes from European capital to capital.

Simone Martini traveled to Avignon in the 1400's, and Hans Holbein ventured in the 1500's from Germany to England. Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin braved the rigors of 16th century roads and made their way to Italy.

JMW Turner, "Castle on the Mosell"

Matisse left his unhappy wife alone in Paris while he painted in Tunisia; Cezanne said goodbye to his exasperated parents in Provence and moved back and forth to Paris.

Van Gogh ventured from Holland to Paris and then to Provence. Gauguin journeyed from Paris to Brittany to Tahiti. Monet, Pissarro and Derain left the banks of the Seine and crossed the channel to work along the Thames.

Camille Corot, "The Colosseum Seen through the Arcades of the Basilica of Constantine"

For hundreds of years, packs of solitary artists have been traveling back and forth across the ocean and over continents.

What were they looking for that they couldn't find at home?

John Singer Sargent,. "An Artist in his Studio"

But even if there weren't clients or cold weather, teachers, students or sieges, artists would still be travelers.

We want to see new things in new ways. We want to shake up our routines of home and family and studio, and be alone where no one knows us enough to break our concentration with a question or demand.

We want that heightened sense of looking, of openness and curiosity, that being in the unfamiliar fosters.

Vincent Van Gogh, "Bedroom at Arles"

When he was a young man, Edward Hopper convinced his parents in Nyack, New York to let him go to Paris to study art.

Through the Methodist church they found him a respectable family to board with, and he painted and sketched in their courtyard until spring came and he could venture out with his easel along the Seine.

Under the influence of the Impressionists and the light of the city, his colors and subjects changed from what they had been in New York. As it had been for so many others before him, Paris was a revelation.

Edward Hopper, "Le Bistro"

When Hopper finally returned for good to Manhattan, he struggled, unsure of what to paint or how to paint it, feeling alien in his own culture. Hopper later said it, "It took me ten years to get over Europe."

Finally this quintessentially American painter left Paris behind, and developed his unique approach to depicting the architecture, light and people of New England and New York.

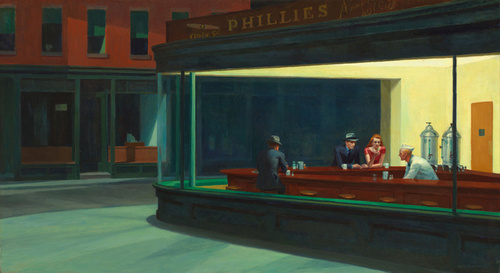

Edward Hopper, "Nighthawks"

In Hopper we can see the gifts of travel, the inspiration, stimulation, novelty, and freedom that being away from the routines of home can provide an artist.

We can also see the challenges of this immersion in another culture.

How do we integrate what we have seen, learned, and felt while away into our life, once we are on familiar ground again?

Paul Cezanne, Mont St. Victoire

An artist's most important trip is the one taken through imagination, that long solo night drive where you see down the dark road only as as far as your headlights.

In this kind of travel, without map or destination, your goal is to just keep moving.

Your comments are welcome below! Feel free to leave your name and website address.