In Praise of Awkward Painting

I’m always amazed by how hard it is to paint, especially painting from perception. It can be one of the most bizarre things you can do. Stanley Lewis

I was lingering not too long ago in the Small French Painting rooms at the National Gallery in Washington, DC when I overheard a man say to his wife, "Our granddaughter could have done that!"

This was accompanied by a snort, so I knew it wasn't a compliment to the painting they were standing in front of, Pierre Bonnard's "Table Set in a Garden.”

Pierre Bonnard, “Table Set in a Garden”

I resisted the impulse to grab the gentleman by the lapels of his well-tailored suit, and tell him just how wrong he was.

I could have given him a point by point explanation of what a sophisticated little painting Bonnard had created, and gone on at some length about complements, diagonals, value design, and color composition.

Pierre Bonnard, “Le Cafe”

I could have asked how his granddaughter was enjoying the immensely productive painting life she had made for herself in the south of France. I could have noted, with admiration, her sixty year dedication to a life of art, and all the sacrifices she had made along the way.

But I’m trying to be a better and less sarcastic person, so I stared instead at a wonderfully awkward portrait by Renoir, and held my tongue.

Auguste Renoir, “Madame Monet and her Son”

Thinking back with a cooler head to that non-painters reaction to “Table Set in a Garden,” I can understand why he said it could have been created by a child. Bonnard's paintings often have that quality.

You can see the brushstrokes in his work, and paint sits on the canvas like paint, rather than becoming an illusion of tree or sky.

Bonnard is more interested in decorative than realistic color, and will often stress pattern over form, which gives his painting its flat rather than three dimensional look, and helps account for its “childlike” quality.

Pierre Bonnard, "Garden in Southern France"

Bonnard's paintings are "not smooth or graceful", which is the dictionary definition of awkward.

Compare this Bonnard figure painting below:

Pierre Bonnard, “Nude in the bath and Small Dog”

to this one by an artist working at the same time in the more traditional “academic” style of the day:

Jules Joseph Lefebvre, “Odalesque”

Did Bonnard have the training and skill set to paint “Odalesque”? No, he did not.

But Bonnard also didn’t want to paint that figure, or paint that painting. From Cezanne and the Impressionists onward, painters were rejecting the idea that illusion was more important than invention, and that gracefulness as defined by art authorities was more important than honesty.

Paul Cezanne, “Still Life with Fruit Dish”

Edgar Degas was a master of the awkward. He painted naked figures rather than nudes, real in their poses and purpose whether combing hair, drying themselves after a bath, or examining their nails and feet like regular women do everywhere.

Degas could have painted Aphrodite with all the skill of a Renaissance master, but choose to paint in a way that was considered ugly by many of the critics of his day.

Degas, “Two Bathers on the Grass”

I find that I have come to prefer awkwardness, and even sometimes ugliness, over prettiness in paintings.

Why? Because I enjoy seeing signs of struggle. I like witnessing the indecision. I don't mind when paint, the physical reminder of the work involved, trumps illusion.

Stanley Lewis, "Two Houses in Leeds", oil on canvas

For example, Stanley Lewis's landscapes, which he works on over many months from observation, are more honest then beautiful. You can see his discarded decisions coming through layer upon layer of pigment.

That residue of time and effort gives Lewis’s painting a power that a more easily achieved image doesn’t always possess.

Stanley Lewis, “View from the Porch, East Side of House”

The British artist Frank Auerbach’s paintings also have a “hard won” quality that I find compelling.

Frank Auerbach, "Rebuilding", oil on canvas

Auerbach painted the same subject a hundred times--and sometimes on the same canvas, wiping down his day’s work when dissatisfied, and beginning again with the same subject the next morning.

The result is sometimes dense and difficult to read, but for me it always carries a conviction of rightness, as if someone looked, and looked again, until every part of the surface was locked into its rightful place.

Frank Auerbach, “To the Studio”

John Constable‘s great landscape paintings also have this sense of being wrestled with. For Constable, emotion, light, the specifics of a sky were more important than generic attractiveness.

Constable talked about struggling with a painting, and not being sure who would come out on top, him or the canvas. I love that image of a fight to the finish in the studio. . . .

John Constable, “Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows”

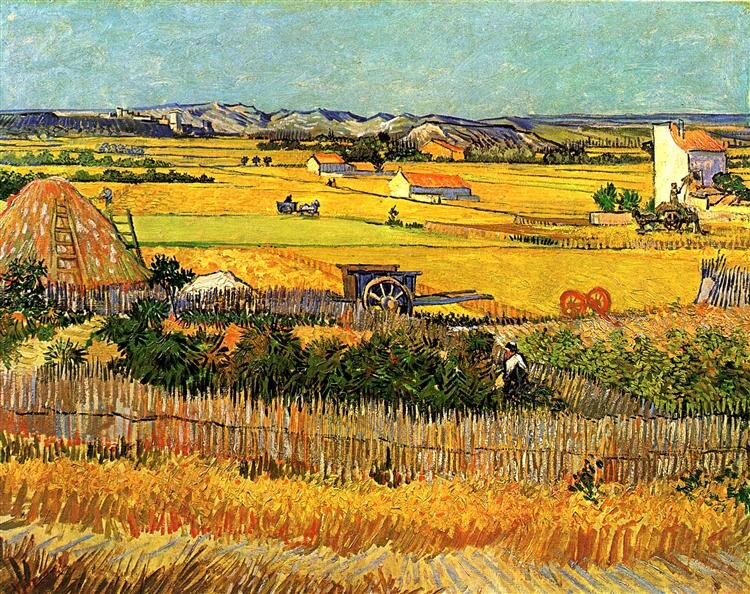

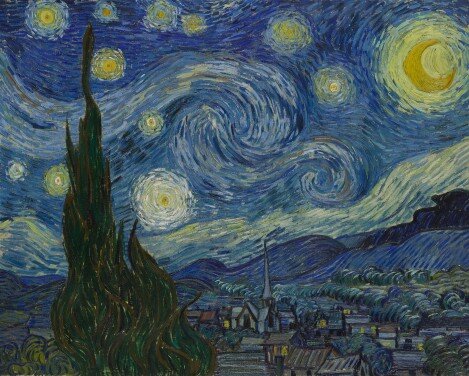

Sometimes rather than through long engagement, an awkward authenticity comes from speed and risk-taking. I’m thinking of Van Gogh, for example, who painted his legendary body of work in less than ten years.

His marks aren’t polished and shapes aren’t refined, but no has created as passionate an evocation of place as Van Gogh does in these Provence landscapes.

Vincent Van Gogh, “Wheat Field with Cypresses”

In my own painting, I’d like to be less afraid of the unlovely, and more open to awkwardness. I’d like to be willing to show less skill and more struggle, more vulnerability and less polish.

I’d like to care less what that man in the gallery would say about my painting, and more willing to share with the world the struggle that got me there.

Other related posts:

Van Gogh’s Methodical Inspiration

Your comments are welcome below!