Purple Houses

I try to apply colors like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music. Joan Miro

Joan Miro

When I'm at my easel outdoors, I'll occasionally get comments from folks passing by. One that always gives me pause goes something like, "Wow, I just don't see all those colors out there that you're using in your painting!”

I'm not too good at talking while I work, so I usually just smile and murmur "Hhmm. . ." But after they walk away, I'll mull it over. I’ll ask myself, "OK, so why am I painting the house purple, and not the grey that guy is sees?"

Susan Abbott, “The Captain’s House, Dusk”, oil on linen

It’s a very complicated question, and I can think about it for a long time, rambling on in my mind about complementary and analogous hues, prismatic value, color composition, and the history of 19th Century art.

Claude Monet, “Haystacks at Noon”, oil on canvas

But sooner or later it occurs to me that there's a simple, one sentence answer to that question regarding a purple house, and here it is: Art is about invention. Like every other creative form, painting is not just copying. It has its own rules, its own life, separate and apart from whatever in the “real world” of nature and man inspired it.

Mimi Robinson, “Color Value Study”, watercolor

In the more abstract art forms of writing and music, it’s accepted that the artist has full range to invent. We know that a novelist does more than describe her next door neighbor as accurately as possible when that person becomes part of a narrative. The writer transforms the neighbor into someone new through the use of imagination, and turns her into a character within a plot.

In the same way, we understand that a composer isn’t just transmitting the sounds he hears around him. Instead, he uses what he hears in a new, individual way, and is given free range to invent his own unique melodic compositions.

Wolf Kahn, “Barn”, oil on canvas

It’s the same for me, and many other painters. Even though we use the world around us as inspiration for our compositions, a painting takes on its own life. The colors on our palette aren’t just tools that enable us to copy exactly what we see in front of us. They are more than that. Colors are the characters that tell our story, the visual notes we string together to form a song.

Susan Abbott, “Blue House by the Inlet”, oil on linen

In a strong painting, color isn’t purely literal, and only there to imitate the things we see. But that doesn’t mean that painters use color in a random, arbitrary way. Colors live by rules. They communicate in predictable ways, and form relationships both complimentary and antagonistic. Colors move and vibrate, and have quiet or aggressive energies.

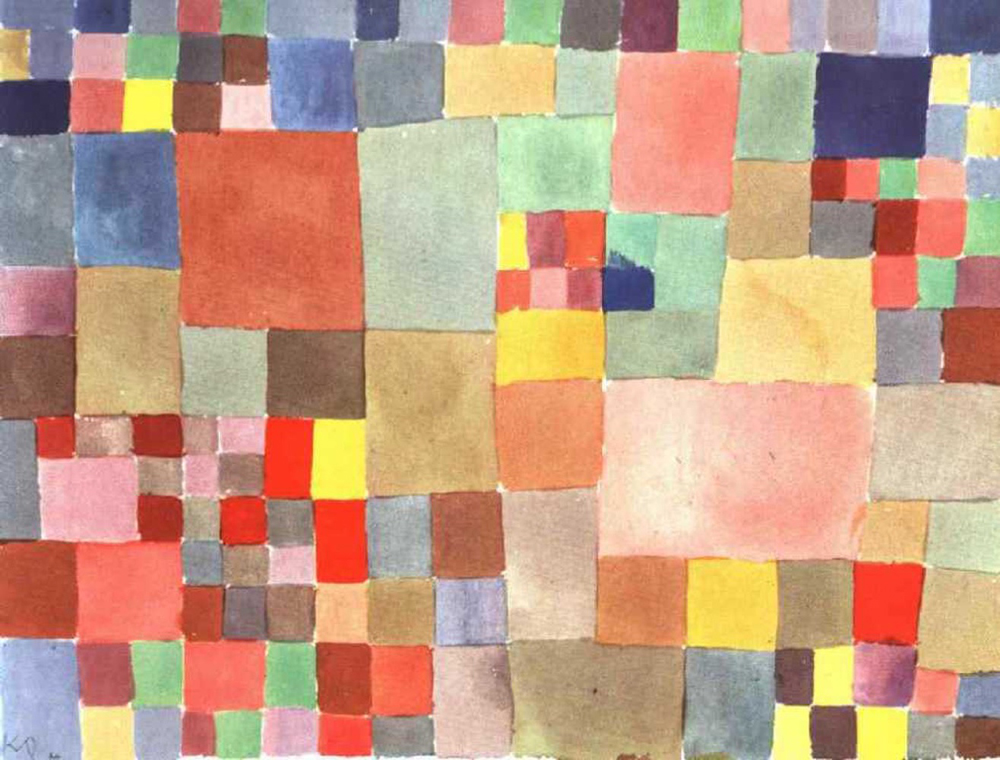

Paul Klee, “Flora on Sand”, watercolor

Blue can make a deep space, or compress it. Yellow can clarify a composition, or confuse it. Red can grab our attention, or hide in plain sight. Green and orange can make us anxious or happy, calm or antsy. And colors do all these things while living on the simple, flat dimensions of paper or canvas. They perform at the service of our brush, once we know the rules of their magic.

Beth Ayres, “Color Value Study”, watercolor

So if I can think fast enough, the next time that guy stops on the sidewalk to watch me paint, and asks, "So why are you making that grey house purple?" I'll respond, "Well, the nice thing about the job I have is that I can paint a house any damn color I want!”

My guess is he'll murmur "Hmmm," smile, and walk away with a good story to tell his wife about the crazy artist he met in town. Meanwhile, I'll be busy mixing on my palette a particularly vivid shade of chartreuse that the purple house requests I use to paint the sky.

Susan Abbott, “Barnyard, Evening”, watercolor

Take a look at these other Painting Notes posts about color: Monet’s Beautiful Murk, Palettes and Place and Mixed Greens.

Your comments are welcome below!