Painters of the Far Away

If minds can become magnetized, mine was: its compass pointed north. Rockwell Kent

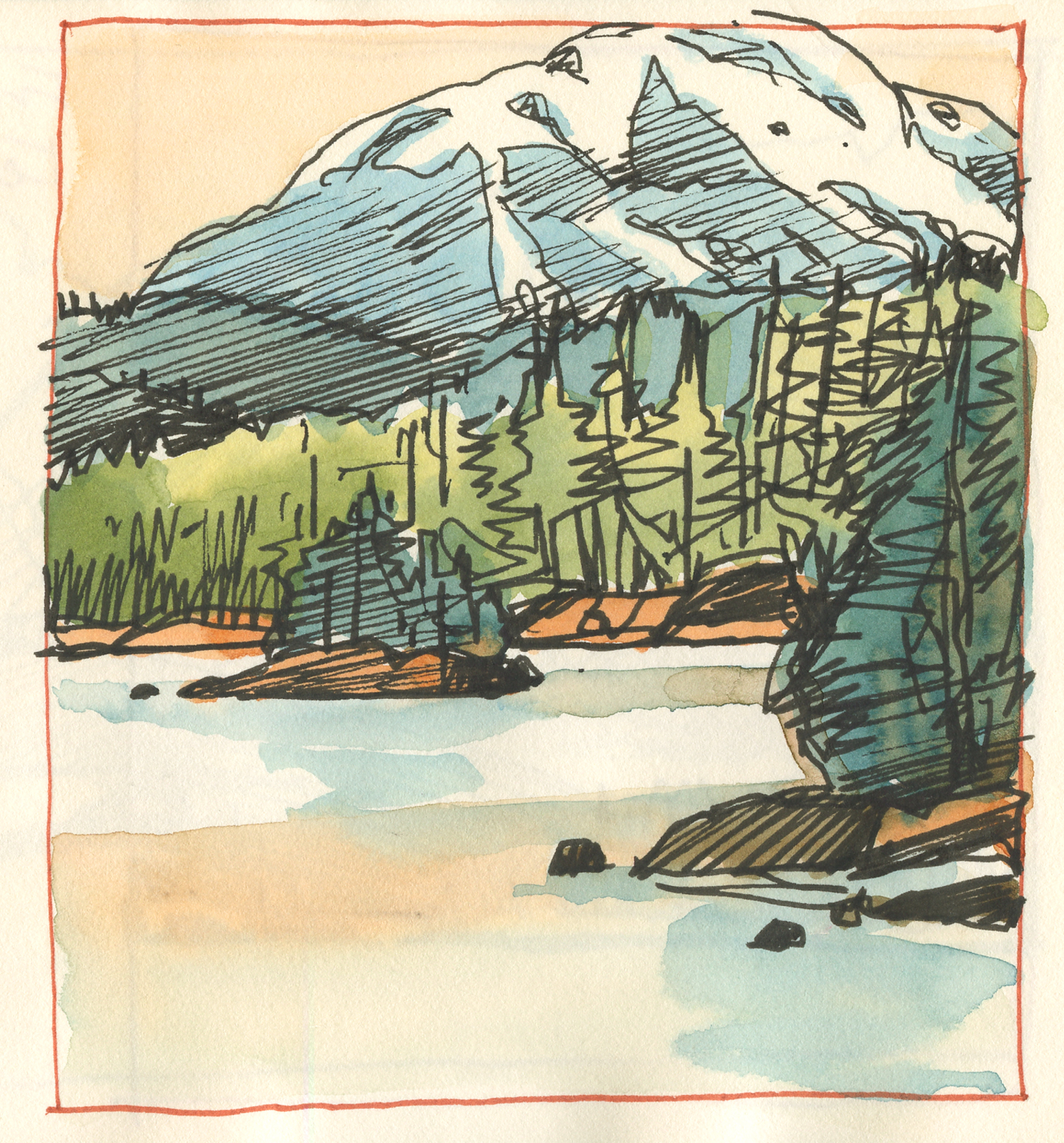

I returned a few days ago from my first ever trip to Alaska, and my head is still full of majestic snow-capped peaks, mysterious spruce forests, and wide open spaces. Since I was in coastal Southeast Alaska, which holds the world’s largest remaining temperate rain forest, my head is also full of watery images of rivers and sea.

I’ve never thought much about how artists have approached painting such a grand and forbidding landscape, but now that I’ve dipped my brush a little bit into these coastal waters, my curiosity is piqued.

Susan Abbott, “Sitka, Cloudy Day”, watercolor

On my trip I was fortunate to have an introduction to the Tlingit community of Klukwan in Southeast Alaska, and learn that the Native people of this area have lived in harmony with their natural home for many thousands of years. Europeans and Americans have been in Native territory for a scant three centuries, but that’s been enough time to have a disastrous effect on indigenous populations.

And yet, the original peoples of Alaska, the Aleuts, Inupiat, Yuit, Athabascans, Haida, and Tlingit, manage to hold on to their ancestral ways of living. They’ve integrated nature and art into their lives in ways we Westerners can only begin to understand, and that we have much to learn from.

Lani Hotch, Tsirka River Robe (Tlingit peoples), textile weaving

When Russians and adventurers from the Lower 48 began trekking ever further north in the 1800’s, they had survival and making money on their mind, not art. Alaska would have been a perfect place for the Hudson River School’s grand, Romantic compositions, but no painters visited (although Frederick Church did journey to Antartica.)

Frederick Church, “The Icebergs”, oil

No painters came until Sidney Lawrence in 1904, that is. Like so many others seeking a quick fortune, Lawrence ventured to Alaska to prospect for gold. When that dream went bust, he dusted off his Art Student’s League training, and became the state’s first successful professional landscape painter.

His paintings are in the “tonalist” European tradition, which sets nature up as a diorama of value gradations from foreground to distance. To our contemporary eye, Lawrence’s work may look predictable and formulaic, but to his contemporaries, his views of this grand landscape were thrilling, and helped define Alaska to the rest of the world as the “last great frontier.”

Sidney Lawrence, “Mt. McKinley”, oil

It’s hard to imagine a painter more opposite in approach to Lawrence than Canadian Emily Carr. True, they both wandered far from home to find subject matter. But Carr was a true maverick, unusual in her time for both her painting style, and how she lived her life.

Emily Carr (1871-1945) rebelled from her very British-style upbringing by venturing to France to study Fauvism, and then to the wilds of British Columbia to learn from the communities of Native peoples who still populated the old growth forests of its coast.

Emily Carr, “War Canoe”, oil

Carr's later paintings reflect her concern with the impact of mining and logging on both British Columbia's landscape and the lives of indigenous people there. Her focus on environmental degradation seems prescient now, given how that activity has accelerated over the last decades.

Emily Carr, “Vanquished”, oil

But Carr also found hope in the enduring power and beauty of nature. And her own life was a testament to endurance. It wasn’t until she reached her sixties that Carr became widely respected as a painter, writer and adventurer, and, finally, an icon of Canadian art.

Emily Carr, “Untitled”, oil on paper

Tom Thomson is another Canadian cultural icon. (You can learn more about his beautiful landscape painting at my post here.) His personal “far away” was the Ontario wilderness, where he painted plein air in all seasons, documenting the changing colors and moods of nature on small wooden panels. Thomson’s view was often intimate rather than grand, a close-up look at meadows and stream, trees and lake.

Tom Thomson, “Yellow Pines”, oil on panel

But he was also drawn to the awe-inspiring, and managed to communicate the mystery and grandeur of the great Northern woodlands on an 8” x 10” scale. In doing so, he awakened in Canadians a new pride in the wild beauty of their country.

Tom Thomson, “Northern Lights, Spring”, oil on panel

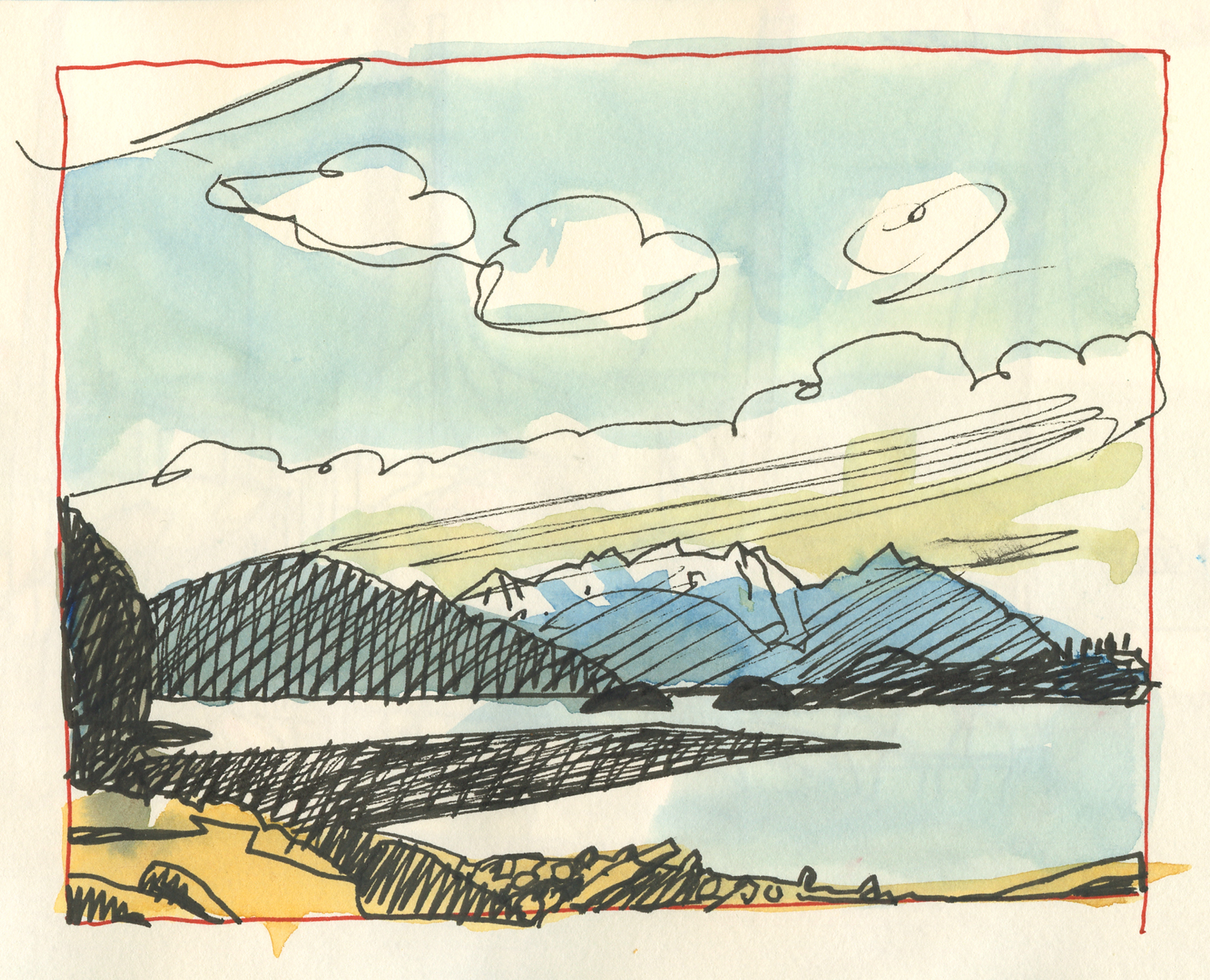

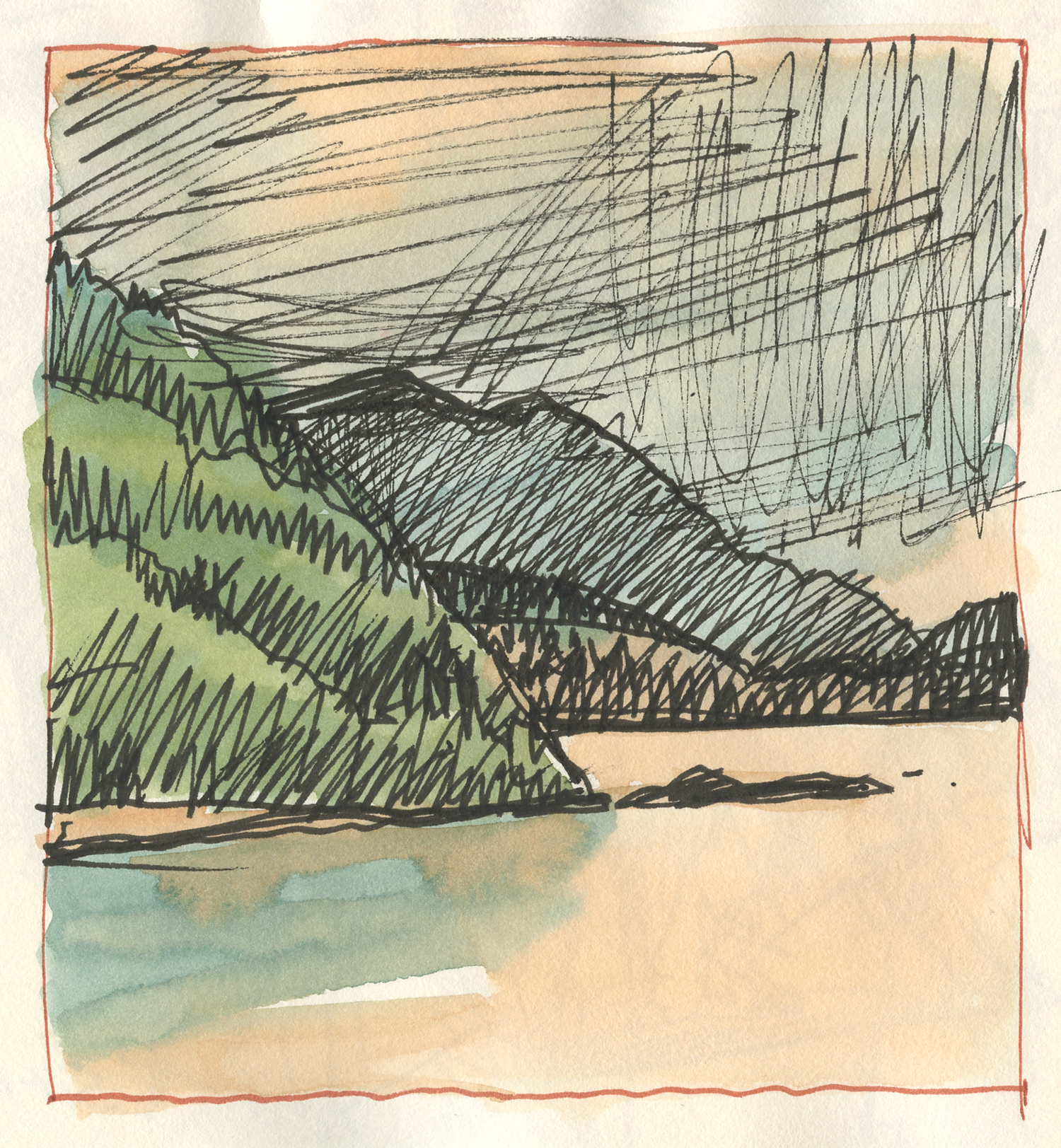

When I was painting in Sitka, Alaska last week, I found my palette was different from the colors I would have used in Vermont, Provence, the Bahamas, or other places I’ve painted plein air.

Just two colors, Prussian Blue and Burnt Sienna, felt right for what I was seeing (with an occasional addition of Yellow Ochre to add a little brighter note when needed.)

Susan Abbott, “Three Mountains, Sitka”, watercolor

In a month or two, where I was in Southeast Alaska will be a much greener place. But in the winter and early spring, blue, brown, and all shades of grey take the lead.

“Frozen North” (detail), Angela Fisher, oil

In his series of paintings of the far away places of the north, American painter Rockwell Kent extracted about the most one can from a tube of brown or blue pigment. Kent took an improbable journey to Alaska in 1918, where he and his eight year old son stayed for seven months in a cabin on a remote island near Seward. (You can read an interesting account of Kent’s time in Alaska here.)

Rockwell Kent, “Alaska Impression”, oil on panel

As a critic said, “Kent’s paintings of Alaska have dazzling blue shades—azure, cobalt, and sapphire—as intense as those van Gogh painted in Arles; you can almost feel the solid ice sprawling over hundreds of miles under the ultramarine sky.”

Rockwell Kent, “Bear Glaciar, Alaska”, oil

After his time in Seward, Rockwell Kent moved to Arlington, Vermont, not too far from where I live. Over the next several years, he continued working on his Alaska series, expanding his plein air “impressions” into large-scale studio paintings.

He never got Alaska out of his head, and even his paintings of cozy New England often have a feeling of grandeur and sweep.

Rockwell Kent, “Nirvana”, oil

Contemporary painters are also drawn to the far away. Richard Estes, who built his career on photorealist New York City landscapes, has more recently turned to a series of paintings of glaciers he saw while on a cruise to Antartica.

Richard Estes, “Antartica” (detail), oil

Vermont painter Eric Aho paints the frozen north in a more gestural way. His compositions edge towards abstract expressionism, but stay rooted in the specifics of landscape, of weather and light.

His subject could be the farthest northern forest, or right near home in the Green Mountains, but you don’t need to know where his inspiration came from to feel the cold.

Eric Aho, “Stag 3”, oil

I hope to discover more about Alaska, its complicated history, spectacular landscape, and rich culture (including the art community) when I’m up there again before too long.

I’m already planning my next trip to the far away.

Here’s information about a new threat to Native culture from a proposed mine in the Chilkat River Valley of SE Alaska. And here’s a creative project environmentalist Elsa Sebastian and filmmaker Colin Arisman (my son!) are working on to help save the Tongass forest from new clear cutting threats.

Your comments are welcome below. If you have any favorite “far away” artists to share, please do!