Connection

Connections were what kept people tied to the world. Without connections, there was nothing left to stop them from simply floating away. Eliza Maxwell

I’ve recently begun a painting series I’m calling “Family History,” and like most times I’ve started a new direction, I’m not entirely sure where the idea came from. One minute my husband was retrieving from a closet a photo album filled with tiny black and white pictures of his parents’ relatives, and the next I was at my studio painting a watercolor of his sister, mother, and grandmother.

“Susan Abbott, Three Generations, watercolor

I know that part of the inspiration for “Family History” is my interest in how figures interact with each other, and with their surroundings. Do they touch, do they keep their distance, bend down to the ground, stand upright, move alone, or in groups?

How do figures connect to the space around them and to each other, and what does this say about their relationship to other people, and to the earth? These may sound like questions for sociologists, but painters also find such ideas endlessly fascinating to explore.

Ben Aronson, Wall Street series, oil

Giotto was one of the first painters to place figures in a realistic space. He creates an intense emotional narrative by overlapping the figures’ forms and by focusing their gaze to make a web of relationships, and a powerful story of connection and betrayal.

Giotto, Kiss of Judas, fresco

In this “Descent from the Cross” by Roger van der Weyden, the figures collapse, hold, lean in, bend, touch. The connection of one to the other tells a story of loss, grief, and the gift of support.

Roger van der Weydon, Descent from the Cross, oil on panel

If you’d like to explore how figures connect within a composition, try looking carefully at a painting and making a quick sketch that focuses on the gestures of the main subjects. No details are needed, just the relationship of figures to each other, and to the space around them. I find this a wonderful way to really see what choices the painter made in connecting figures, and the emotional resonance those decisions create.

Susan Abbott, Madrid sketchbook, sanguine and black Pitt pen

When I travelled in India I was struck by how the people there relate physically to the earth, and to each other. Sitting on the ground, squatting, bending down are normal postures there. Indians stand closer to each other, touch each other more, watch each other intently in a way that we in the United States would consider impolite, or even threatening. But in India the result of all this physical contact seemed to me to create a feeling of community, of connection to place and to each other.

Susan Abbott, Street Market, Rajasthan, oil on paper

Not all figures in painting—or reality--connect. Sometimes they are like atoms, separate and distinct, on the alert and keeping their distance, dwarfed by their environment.

Hurvin Anderson, Red Flags, oil

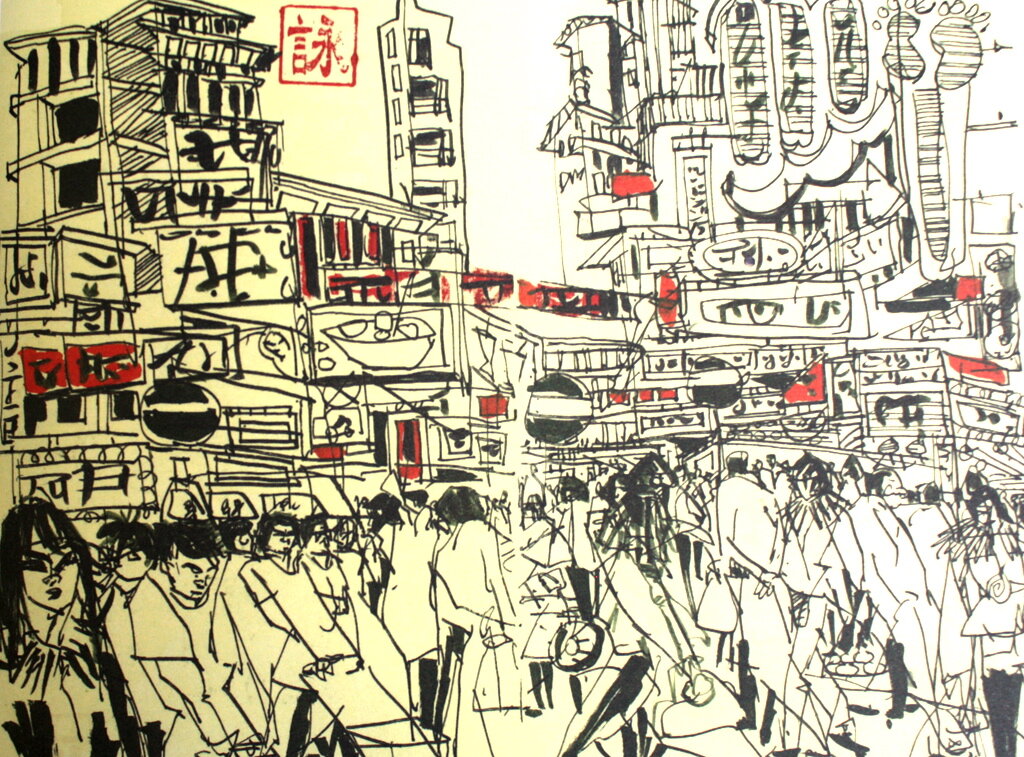

In cities we keep our distance with upright posture and purposeful gait, maintaining around ourselves a zone of privacy . A city environment is also upright, all right angles and unyielding surfaces.

Ben Aronson, Urban Reflections, oil

Unless you are homeless and sleep on the street, in modern cities only your feet touch the ground.

Melanie Reim, pen in sketchbok

Our wealth, or lack of it, can determine our physical connection to both family and the strangers around us. The poor can’t afford to keep distance in a home or a city, as George Bellows showed in his paintings of New York tenement kids. Individual figures become one mass of light values and warm colors in his painting “Riverfront”.

George Bellows, Riverfront, oil on canvas

All through the history of art, painters have wrestled with the theme of figures in a landscape. A favorite subject, revived by Paul Cezanne in the 1800’s (though out of fashion now) is the Arcadian idyll that features idealized figures in a bucolic setting.

Resting or dancing, grounded and comfortable, their postures communicate peace and connection.

Paul Cezanne, Grand Bathers, oil on canvas

In the idyll, human and nature are at peace and as one. Landscape and figures share the same shapes, light, and colors, and it’s difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins.

Paul Cezanne, Bathers, watercolor

Figures in a natural setting can also be delineated by the shapes between them, or what artists call “negative space.” Negative spaces are as flat and definite as a jigsaw puzzle piece, and because they are abstract and engage our “right-brain,” are a huge help in drawing the figure.

In Fairfield Porter’s painting “Tennis Game,” the negative shape of the tennis court pins the figures into separation, and into a relationship very different from the connection shared by Cezanne’s and Bellow’s bathers.

Fairfield Porter, Tennis Game, oil on canvas

For visual artists, the shape of the negative space between figures is a precise calculation.

Reggie Burrow Hodges, In the Service of Others, oil on canvas

Whether two figures merge, or are defined by the shape between them, tells us either a story of separation or connection.

Maybe saying “tells a story” is too definite for visual art. I’d do better to say that the artist’s choices “ask a question” about separation and connection.

Arshile Gorky, Two versions of The Artist and His Mother, oil on canvas

Painters can use their skill to create something in-between isolation and connection that’s very much like life.

A painting can remind us that our relationships with others, even those closest to us, hold mysteries.

Susan Lichtman, Interior, oil on canvas

Which brings us back to family, and what painting, with its language of shape, light and color, can say about a family’s connections, and to the place that family calls home.

I don’t know the answer, but I’m looking forward with my “Family History” series to exploring the question.

Susan Abbott, Swimming Pool, watercolor